The attack methods serious cybercriminals use are often so sophisticated that even cybersecurity pros have a real hard time uncovering them. A while ago, our experts detected a new campaign by a North Korean group called Lazarus, notorious for its attacks on Sony Pictures and a number of financial institutions — for example, a $81 million theft from the Central Bank of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh.

In this particular case, the intruders decided to line their pockets with some cryptocurrency. To get to their victims’ wallets, they dropped a piece of malware into the corporate networks of a number of crypto-exchanges. The criminals relied on the human factor, and it paid off.

Trading application with a malicious update

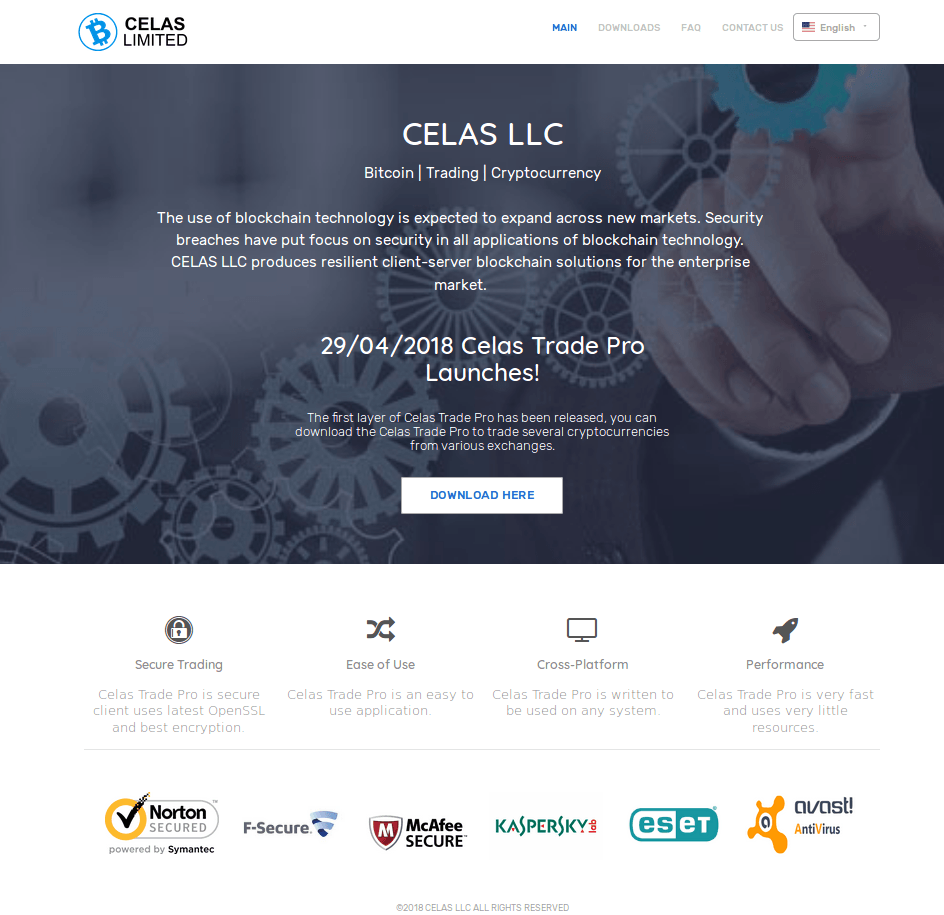

Network penetration began with an e-mail message. At least one of the crypto-exchange employees got an e-mail offer to install a trading app called Celas Trade Pro by Celas Limited. A program like that might potentially be of use to the company, considering its corporate profile.

The letter included a link to the developer’s official website, which looked fine — it even had a valid SSL certificate issued by Comodo CA, a leading certification center.

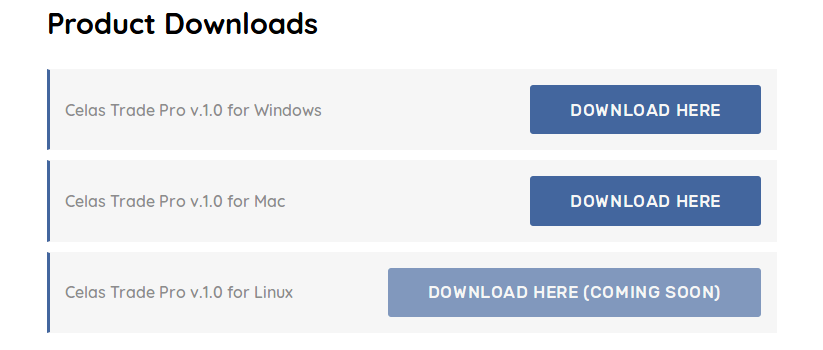

Celas Trade Pro was available for download in two versions: for Windows and Mac, with version for Linux coming soon.

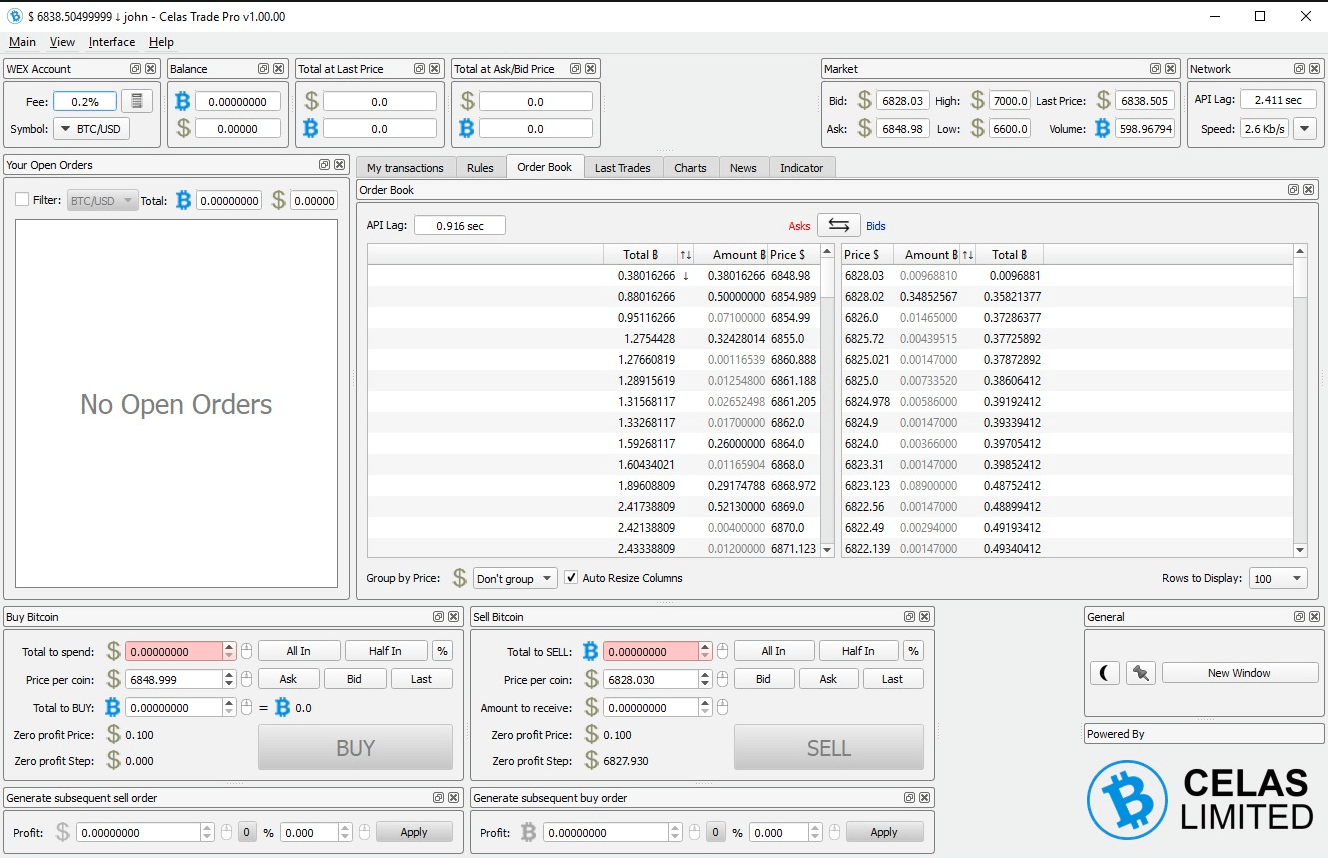

The trading app also had a valid digital certificate — yet another legitimate product attribute — and its code contained no harmful components.

As soon as it was successfully installed on the employee’s computer, Celas Trade Pro initiated an update. For that it contacted the vendor’s own server — nothing suspicious there, either. Yet instead of an update, the device downloaded a backdoor Trojan.

Fallchill: Very dangerous malware

A backdoor is a virtual “service entrance” criminals can use to penetrate a system. Most of the previous attacks on exchanges were accomplished using Fallchill. Along with some other signs, Fallchill was the key piece of evidence pointing at the attackers; the Lazarus group had used this backdoor more than once before. It allows almost unlimited control of the infected device. These are just a few of its features:

- Searching for, reading, and uploading files to the command server (the same one the trading software used to download its update);

- Recording data to a particular file (e.g., any.exe file or a payment order);

- Wiping files;

- Downloading and executing additional tools.

A closer look at the infected program and its makers

As we already explained, both the trading software and its vendor maintained quite a respectable appearance almost all the way through the attack — at least, until the backdoor was installed. However, upon closer scrutiny, suspicious details emerge.

For starters, the update loader was sending the machine info to the server in a file disguised as a GIF image and was receiving commands the same way. It’s not at all typical for serious software to exchange pictures in the course of updates.

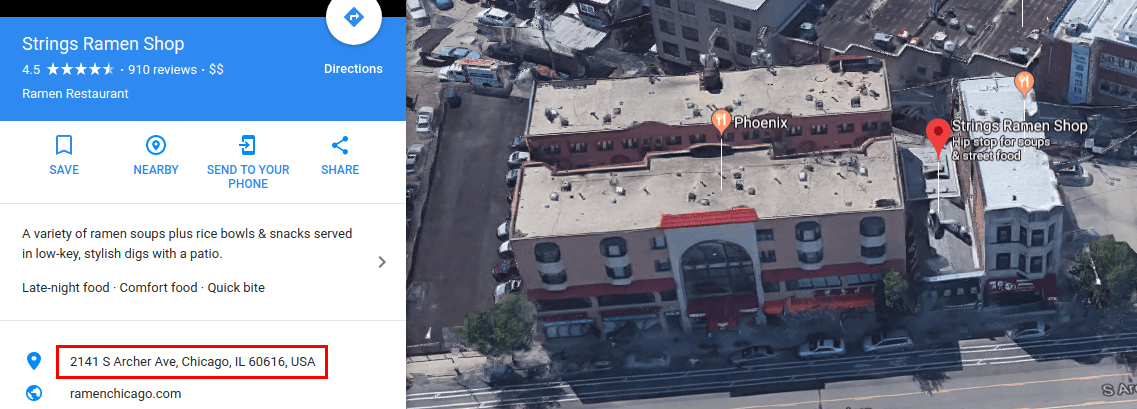

As to the website, on closer examination, the domain certificate turned out to be a low-level one, confirming nothing but the fact that the domain was owned by an entity called Celas Limited. It contained no information about the company or its owner (more advanced certificates imply these verifications). The analysts used Google Maps to check the address used for the domain registration only to find that it belonged to a single-story building housing a ramen outlet.

It being unlikely that the little restaurant owners used their spare time for programming, the logical conclusion was that the address was a fake one. Nevertheless, the analysts checked the other address specified for Celas Trading Pro’s digital certificate, and found it was an empty field.

In addition to that, the company had apparently paid for its domain with bitcoins. Cryptocurrency transactions are favored when anonymity is required.

And yet, we cannot be certain whether this company is a purpose-built fake or a victim of cybercriminals. The North Korean hackers have a history of compromising legitimate organizations for the sake of attacking their partners or customers.

You can read more about the APT Lazarus campaign in the full report by our experts on Securelist.

Lessons learned from the Lazarus case

As the story suggests, it may be very hard to figure out the source of a threat when big money is at stake. The cryptocurrency market is particularly popular of late, attracting scammers of all sorts: from developers of all manner of miners to serious criminal groups that are at work all over the world.

The campaign’s broad target is of particular interest: It has targeted not only Windows users, but also macOS computers. It’s another reminder that macOS is no guarantee of security — Apple users, too, have to ensure their own protection.

threats

threats

Tips

Tips